1. About this Guide

The Guide for Inclusive Communities analyses how to use community-based entrepreneurship learning as a tool for inclusion of young migrants and refugees in local communities. It looks at the effects of the entire project on inclusion, as well as at the impact of learning throughout the project and how it can contribute to building inclusive communities. It is designed for policy makers, local stakeholders, youth workers and all those interested in the topic Inclusive Communities.

The Guide highlights best practice examples of the Welcomeship Course combined with skills and competences gained through idea development, implementation and collaboration with community stakeholders. An important part of this Guide are the policy recommendations which cover the local, regional, national and the EU level. These recommendations are based on research, feedback, input and involvement of local policy makers and politicians through surveys, Welcomeship Nights, video interviews and regular local and international meetings. Those recommendations have been enriched through the feedback of local teams and young people. That was received in the project meetings and discussed at the multiplier events with wider audience and associate partners.

This is what makes this Guide for Inclusive Communities innovative:

- It is based on the input from local stakeholders involved in the project, such as young migrants, refugees, local youth, community stakeholders, project teams and local politicians. This reflects the “bottom-up” approach based on real life experiences.

- The online version of the Guide in English, which is published on the Welcomeship Channel in the section Policy Change, has interactive features: users can add resources, information, comments and questions, so the Guide becomes a living resource that is enriched over time.

- The Guide for Inclusive Communities is available in English, German, Italian, Portuguese and Swedish in PDF format on the Welcomeship Channel.

- The online version is enriched through a range of interviews with young people, youth workers, community stakeholders and policy makers from project countries.

- Policy recommendations, developed by the local stakeholders and experts, may be used as an advocacy tool to influence policies at a local, national regional and EU level.

Along with the Welcomeship Channel and its entire content, this Guide is an essential instrument within the efforts to improve policies advancing the situation of young migrants and young people with fewer opportunities. It is designed to have an impact on several target groups: from young people and youth workers to community stakeholders, civil society, public services and policy makers. The Guide promotes non-formal learning, voluntary activities, participation, youth work, information and mobility. It contributes to mainstreaming community-based entrepreneurship learning as a tool for inclusion. It encourages cross-sector initiatives that ensure that youth issues are taken into account while formulating, implementing and evaluating policies, actions and calls for consulting youth in the fields that have a significant impact on them, such as participation, education, employment, health and well-being.

2. Key terms of the project

Some of the key terms used in the Welcomeship project and in this Guide for Inclusive Communities are outlined hereafter in order to facilitate understanding and avoid misinterpretation.

2.1. Welcome-ship

The project Welcomeship combines 2 key concepts:

1) WELCOME stands for the creation of a welcoming culture in local communities and in society as a whole. The German concept of welcoming culture „Willkommenskultur“ means a positive attitude of politicians, businesses, educational institutions, sports clubs, civilians and institutions towards foreigners, including and often especially towards migrants.

2) SHIP stands for entrepreneurship and entrepreneurship learning. The aspiration of Welcomeship and our assumption tested in this project is that a welcomeculture and the inclusion of young migrants and refugees can be fostered through entrepreneurship, and community-based entrepreneurship in particular, to involve young migrants, refugees, as well as other young people and community stakeholders.

2.2. Migrants & refugees

According to the United Nations, an international migrant is someone who changes their country of usual residence, irrespective of the reason for migration or legal status. A refugee is a person who is outside their country of origin for reasons of feared persecution, conflict, generalized violence, or other circumstances that have seriously disturbed public order and requires international protection.

While both groups have very different circumstances and needs, the main target group of the Welcomeship project is composed of both young migrants and refugees and even young people with migrant background (second generation – children of immigrants).

One of the reasons these groups were invited to the project is that both groups suffer from prejudice, racism and social exclusion based on their origin or the origin of their families. In addition, the course groups would include young people without migrant or refugee background in order to learn, exchange and work in groups of mixed background as opposed to isolated groups of exclusively migrants and/or refugees.

2.3. Inclusion vs Integration

Social inclusion in the project refers to full economic, social, cultural, and political participation of migrants in the host communities. Integration occurs in the public and private realms, across generations, and at the individual, family, community and national levels (EU Council, 2004).

As the subtitle of the Welcomeship project indicates – Building Inclusive Communities through community-based entrepreneurship – the project aims at the inclusion – as opposed to integration only – of young migrants and refugees.

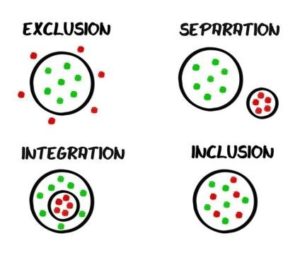

The graph on the right clearly illustrates the difference between Inclusion and Integration.

The graph on the right clearly illustrates the difference between Inclusion and Integration.

Welcomeship aims at the empowerment and repositioning of young people through new skills and competences gained in the Welcomeship project. It also strives for a structural and policy change in the local communities through advocacy work towards policy makers, and the change of mentality and attitudes, as well as the way stakeholders and community members perceive young migrants and refugees (“from passive victims to active change makers”). So, the aspired positive change is at the level of the target group, the host communities and the society as a whole.

2.4. Inclusive communities

While everybody has its own definition and idea of what an inclusive community is and should look like, most would agree that an Inclusive Community is a community in which its citizens and members feel safe, respected and comfortable in being themselves and expressing all aspects of their identities. It is certainly also linked to structures and services that are accessible to all members of society regardless of cultural and ethnic background, religious belief, sexual orientation, disability, etc. An inclusive community has open-minded citizens, and organisations and institutions that embrace diversity.

What it means to each project participant was addressed in the first Module (M1 – Opening Minds & Doors) of the Welcomeship Course and was thoroughly discussed and debated. This was an important part of the project where topics, such as Diversity, Inclusion vs Exclusion and what it takes to build inclusive communities were worked on in depth before Modules 2,3,4 and 5, which were focused on community-based entrepreneurship.

2.5. Community-based entrepreneurship

There are many types of entrepreneurship: business, social, female, solo, environmental or scalable start-up entrepreneurship. What is meant by community-based entrepreneurship in the context of the Welcomeship project is defined below. Key elements:

- It starts with a situation analysis of a community in order to determine social issues and problems or the needs of community members, as well as resources, key players and potential partners.

- The entrepreneurial ideas developed are based on this analysis and represent a solution to the social issue or respond to a need in the community (as in social entrepreneurship). It is also sustainable and aims at bringing about positive social change to the community.

- For the development of the entrepreneurial idea, the entrepreneur sets up partnerships in the community in order to work in collaboration with other community stakeholders to address the needs in the community.

2.6. Why community-based entrepreneurship for inclusion?

The overall goal of the project is to develop, implement and test the “Welcomeship” model” – a model of entrepreneurship learning for young people with fewer opportunities, including young migrants and local youth. The “Welcomeship” model is based on non-formal learning methods and collaborative practice. It strengthens the interaction of locals and newcomers, addresses fears and prejudices, and fosters community spirit as an overarching goal. Local youth and young migrants develop entrepreneurial ideas addressing community issues and build partnerships with stakeholders to bring about positive change in the local communities. This collaboration is intended to lead to openness, tolerance and an atmosphere of togetherness in the community. Ultimately, the “Welcomeship” model aims at becoming a tool for inclusive communities.

3. Key resources used to produce this Guide

A wide range of resources and approaches have been used from the onset of the Welcomeship project. First it was data collection from young migrants and refugees, trainers of the project, community stakeholders and policy makers. The aim was to get a wide range of perspectives and to investigate if the idea of investing in community-based entrepreneurship learning pays off and contributes to an inclusive and coherent society. Through this range of channels, resources and actions we were able to provide policy recommendations for the local, regional, national and EU level.

3.1. Overview

- A survey was conducted among young migrants and partner organisations at the beginning of the project to find out about their perception of how inclusive their community was, and their interest in entrepreneurship learning.

- An Advocacy Strategy for the project was defined among all partners of the project. It resulted in the set-up of the local action plans, where each partner set the indicators on how to foster entrepreneurship for inclusion and influence local policies.

- Welcomeship Nights were organised by the project partners to invite community stakeholders, including policy makers. These nights had different formats (Entrepreneurship Labs, community gettogether, pitching nights, intercultural nights, talk shows, etc.) and aimed at promoting community-based entrepreneurship as a tool for inclusion, fostering exchange between young migrants (enrolled in the Welcomeship course) and community stakeholders, and influencing policies by debating them with stakeholders and policy makers.

- Feedback about the implementation of the course was gathered from young people and trainers through evaluation forms in each of the 5 Welcomeship Modules.

- Advocacy videos of participating young people and trainers, as well as community stakeholders and policy makers, have been produced in the form of video interviews.

- A survey at the end of the project was made among all partners of the project in order to gather best practice and policy recommendations.

- Through the Welcomeship Forum in the Policy Change section and the Welcomeship Twitter account, an advocacy campaign was launched to inform and engage the audience on policy related issues with regard to entrepreneurship and the inclusion of migrants on a European level.

- During all international meetings (project meetings and blended mobility events), evaluation surveys were conducted in order to get the view of participants on policy related issues.

- A thorough analysis of EU policy landscape has been made by project partner Out of the Box International.

3.2. Welcomeship Channel

The Welcomeship Channel has been developed as Intellectual Output 4 for the following strategic purposes:

- It is a website where all relevant information about the project, all Intellectual Outputs, project-related videos and interviews, as well as evaluation reports, are published and can be found.

- It has an integrated online learning platform where participants of the Welcomeship project access all course-related elements, such as texts to read and tutorials to watch. It also gives the opportunity to exchange with peers through interactive features and to upload homework. It is available in five languages (English, German, Italian, Portuguese and Swedish) and there is a trainers’ section where all exercises (more than 100 in total) are available for each of the five modules.

- Last but not least, it serves as an advocacy tool with the aim to influence local, national and EU policies in relation to entrepreneurship learning and the inclusion of migrants and refugees. In the Policy Change section of the Welcomeship Channel, people can find: 1) the Advocacy Strategy of the project, 2) a Forum linked to the project Twitter account. In the Forum and on Twitter, policy-related information is posted on a regular basis, promoting entrepreneurship and the inclusion of migrants and refugees showcasing best practice examples, news on the EU policies, the latest statistics and any relevant information with the aim of promoting entrepreneurship as a tool for inclusion. 3) The Guidebook for Inclusive Communities is published as an online version with integrated videos and interactive features (comment sections), as well as translations into German, Italian, Portuguese and Swedish as PDF files.

3.3. Advocacy strategy

During the first months of the project, the consortium of partners of the Welcomeship project has developed an Advocacy Strategy along with an action plan.

The Welcomeship project aims at advocating at a local, national and European level for community-based entrepreneurship as a tool for building inclusive communities. The following general key advocacy results aim at mainstreaming of community-based entrepreneurship as a tool for the inclusion of young migrants and refugees. They are promoted by all partners of the project during the entire duration of the project:

- Community-based entrepreneurship is being mainstreamed for promoting inclusive societies to make local authorities, public institutions, schools, CSOs, youth centres, and SMEs more aware of the concept;

- Partners build coalitions with like-minded organisations or institutions with the same interest on the local and European level;

- Partner organisations are recognised as facilitators of the community-based entrepreneurship ecosystem, which means strengthening a network of resources, policies and entrepreneurship stakeholders to create a more favourable environment for entrepreneurial ideas to thrive.

Partners strive to reach the following advocacy targets, supported by the lead organisation and the partner responsible for this task:

- The advocacy activities for concrete initiatives and programmes supporting community-based entrepreneurship are being conducted at the local level. The idea has reached policy makers. Partner organisations are recognised as valuable contributors in this process. Young people are consulted and involved;

- Increased opportunities and resources are created at the local level for young people with migrant background and local youth to engage and create new community-based entrepreneurship initiatives;

- Motivated groups of youth entrepreneurs with migrant backgrounds in collaboration with local youth are created and they actively work on generating new ideas for community-based entrepreneurship as a step towards a change of perception of the community towards migrants and refugees.

4. Welcomeship Course: tools for inclusion

This chapter outlines the lessons learnt from the Welcomeship Course and is based on the evaluation reports from partner organisations, as well as group evaluation sessions during partner meetings. It focuses on trainers’ and coordinators’ feedback to the course modules, especially the introductory module “Opening Minds & Doors”; the role of values, expectations, fears and prejudices in intercultural learning; it presents the examples of how intercultural dialogue was encouraged through the project and outlines the lessons learnt from the project.

4.1. Introductory Module “Opening Minds and Doors”

The introductory Module “Opening Minds and Doors” was very important for the community-based entrepreneurship course, or, as most trainers put it, the most important. It addressed team building, identity questions, diversity and social justice, as well as community development and spirit. Creating a common ground aligned participants with the values of the project, gave them common roots and allowed to get to know each other’s backgrounds and experiences.

“When you get to know each other, it is easier to work together and set standards and rules for the group work.” (Youth Office Kristinestad, Finland)

The exercises of listening, respecting and valuing each person’s opinion laid a positive fundament for the continuation of the course. It helped participants to create trust and authentic bonds in the group. They felt safe and comfortable to share their opinions. They also became aware of the power of social identity and what it takes to collaborate beyond stereotypes and norms.

“Such an approach enabled honest learning. Young people could explore the differences between cultures, as well as barriers. We clarified concepts like diversity, multiculturalism and community, and created bridges for a smooth and meaningful dialogue where each individual was respected and had his/her space.

This module helped young people to discover different perspectives and understand that they may perceive themselves in a way different to others”. (DYPALL, Portugal)

Deviation from the standard entrepreneurship course with the first module on inclusion did not work for the people interested solely in entrepreneurship, as it was a case with the first group in Turin, Italy. Participants who came first got a wrong image of it and did not turn up again so the group needed to be restructured.

The biggest achievement of the Module “Opening minds and doors” was that it laid a fundament for intercultural learning within the group. Reflecting on identity and values in a group with many different cultural backgrounds led to participants’ better understanding of themselves and created more empathy and understanding of others’ behavior. Without addressing the values and subsequent prejudices that many communities have (including the majoritarian community), mutual learning would not be possible. As trainers reported, sharing expectations, fears, as well as hopes and dreams, made young people think more of what is common instead of what is not. Ultimately, the interpersonal focus of the Course helped group members to develop a feeling of unity, a common vision towards the values of tolerance, kindness, friendliness, respect, equality, and dignity; to see diversity as enriching and inspiring, and experience Oneness through joint learning, travels and collaboration.

Fears and prejudices are part of the human experience. Fears emerge when confronted with the unknown, prejudices arise and are being fostered and maintained out of a mindset of scarcity of lack of resources, a belief that there is not enough for everyone. Intercultural learning is a great tool to confront limitations based on prejudice and fear, and allow both to dissolve. (Migrafrica, Germany)

4.2. Intercultural dialogue and mutual understanding

The project inspired new ways of encouraging intercultural dialogue and building mutual understanding between newcomers and partner communities, in particular:

- Youth-led podcast on the inclusion topic in Albenga was created

- New workshops and conferences on the topic of integration and inclusion were held in Albenga

- A course was delivered in comfortable and safe settings for both the locals and people with migrant background in Portimao (Beach point) and Kristinestad (Youth garden)

- A rule to disagree agreeably – when a not so consensual topic was discussed in Portimao – led to building bridges of common understanding and broadened the perspective of young people

- Participants were sometimes asked questions that would take them out of their comfort zone, e.g. find different perspectives, mix beyond mutual language and culture or similar biographies in Portimao and Cologne

- Local residents were involved in the activities and practical exercises for experiential learning in Kristinestad

- A safe space was created to practice a new language for the newcomers –reminding native or fluent speakers to be aware of the speed of their speech, as well as encouraging those who were insecure in the use of a certain language to use the space in Cologne and Kristinestad

In Portimão, there are communities of young people whose parents come from former Portuguese colonies in Africa: Mozambique, Cape Verde, Angola and Guinea-Bissau. Young people might never have visited their country of origin, so they cannot identify with it, and at the same time they feel different to the native Portuguese people. This creates somewhat of a double consciousness of being “Portuguese with a different background”. This is a similar situation to many Brazilian young people who were either born in Portugal or came recently. Even though they all speak the same language, their paths of life bring them, often, to different places, opportunities and choices (DYPALL, Portugal).

4.3. Learning for inclusion

When asked, how do the learning elements of the Welcomeship Course contribute to inclusion in your community, the teams stated that it is the combination of the elements that works, in particular:

- Reflection on the concepts, such as culture, identity, values, prejudice, including reflection on your own identity and biases,

- Awareness of differences, abolition of judgment and management of possible intercultural conflicts within the group,

- Team building exercises to strengthen the feeling of belonging to a group,

- Meetings with local residents, leaders and entrepreneurs to get to know each other and discuss the ideas of young people

- Community mapping to learn to recognize and respond to the community needs

- Exercises that foresee team work and finding a way to communicate with each other regardless of the language, cultural and ethnic barriers

- Site visits, online learning and meetings with NGOs and businesses to see positive examples of inclusion and inspire the group to create their own ideas

Whereas we did not have so many local people attending the course at the end, we got a lot of attention when we organized the Culture Café on the weekend. Some people were a little hesitant to attend, but otherwise a lot of local residents thought that it was a great opportunity for them to learn about different cultures and meet people with migrant background. (Youth Office Kristinestad, Finland).

Entrepreneurship learning contributes to inclusion because young people from wherever they are in the world are creative, they have ideas, they are flexible and they take risks. When young people from other parts in the world come to London, they have taken risks, because they don’t know what they are going to be facing. I think that entrepreneurship learning allows for young people to work together and as an entrepreneur to start your own journey. (UBELE, UK)

4.4. Improving policies

In the opinion of the trainers and coordinators, the project’s contribution to improving the situation of young migrants and young people with fewer opportunities has been in:

- a) establishing an inclusive social network where migrants and local people could come together, learn and collaborate;

- b) giving young people skills and tools to create their business;

- c) providing a space to voice young people’s opinion, also in front of policy makers, to raise awareness of societies to become more inviting and tolerant,

- d) getting involved in public consultations on youth issues.

The project created spaces and opportunities for young people to learn and study in an inclusive environment and experience a rich diversity, which is a valid and crucial factor to inclusion. While improving policies takes a while, this practical experience of community stakeholders and young people getting closer to each other set the tone for mutual understanding and strengthened the wish to improve the situation of young people with fewer opportunities.

More than improving policies, the project opened some minds and overcome some obstacles. This was a first step to improve policies at the local level, a process which usually requires time. The project allowed people to reflect about the obstacles that certain groups face in a very clear way, and it created more tolerance and understanding among different stakeholders and policy makers. It was important to give the floor to young migrants, people with migrant background or young people with fewer opportunities for them to explain the different obstacles they encounter, as well as the opportunities they see (DYPALL, Portugal).

To give a few examples: Young people from the Welcomeship groups got in touch with policy makers in Kristinestad: they presented their vision to a mayor, e.g. what kind of a city they would like to live in. For the vision, they took ideas from their hometowns around the world and cities they transited while fleeing from their home country to Finland. Another chance to voice their opinions was during the consultation on the welfare programme initiated by the municipality, where young people met a politician to discuss youth issues. In Portimao, young people were involved in the creation of the Youth Municipal Plan conducted by the DYPALL Network together with the Municipality of Portimão. In Turin, the municipality gave its patronage to the project and hosted project meetings in the premises of the Intercultural Center, and also helped to disseminate project results.

An important success factor was that the municipalities where the project was implemented were quite collaborative and there was already a history of cooperation. It got stronger through the project since municipality representatives were involved in project activities, e.g. meetings with young people, Welcomeship Nights, interviews, Talk shows, youth exchange in Albenga, and Multiplier events.

These activities raised awareness of policy stakeholders about the experience of local reality by young people with different backgrounds. Whereas the Municipality of Turin is already aware of and active on these issues (see for example the interview by Youth Policies Delegate Marco Alessandro Giusta), in Portimao, Welcomeship will influence further creation of policies and development of activities and actions that target multi-ethnic communities. In Albenga, the wish for the next step is to extend the social network created in the project to the whole community, and attract further ideas on inclusive living, as well as know how and funds.

4.5. What worked well in Welcomeship

- Group diversity. Having a mixed group – of people with migrant background and local roots – created a perfect environment to promote intercultural dialogue and strengthen common understanding of the context. The only way to an inclusive society is when all parts of the community come together to understand the different perspectives.

- Welcomeship Nights: giving the power to young people to lead these events, discuss the topics of major importance to young people with the local stakeholders and connect them around those topics has been a truly empowering experience.

- Experiential activities, such as site visits and meetings with entrepreneurs, were the highlights in local trainings, and lowered the language barrier for those who were not so fluent in the workshop language.

- Experiential games, like “Insider/Outsider game” from the Exercise Book, or “Step forward”, shifted the perspectives of the group as it made them walk in someone else’s shoes and strengthened their understanding, compassion and tolerance.

- Skills training, like communication, pitching, business model canvas, both in local training and international youth exchange in Albenga, was rated very high by young people.

- Blended mobility for young people / International youth exchange in Albenga: for most young people, it was their first international activity and had a big impact on them: they got to know people from all the partner countries and the stories and paths of the different participants. After the youth exchange, the groups came back very excited and motivated.

- Mixed group work to create and test entrepreneurship ideas.

A practical example of the application of the Welcomeship tools, combined with the model of collaboration between migrants and local young people, is a concept of a fusion restaurant with African and German food, which was tested in Cologne and may result in a real community project. (Migrafrica, Germany)

- A new social network of contacts and interactions strengthened the feeling of belonging to the community.

A lot of young people in our group already have a lot of skills, but they are lacking the network of connections. This project enabled them to access these connections, which was very empowering, and they gained the confidence to do what they wanted to do. (Solna Youth Café, Sweden)

4.6. Impact on young people, community stakeholders and a community

According to the course evaluation, young people who were actively involved in the Welcomeship course, felt more empowered towards the end of the course and developed a bigger sense of belonging to and responsibility for their community. The general satisfaction of course participants is high (for example: in Turin, 70/100 on average). A course of five modules on how to set up their own business and how their business can promote inclusion and sustainability in their communities equipped young people with multiple skills (communication, empathy, tolerance, business planning, community analysis, pitching, project management, etc.). Many participants claimed to have changed their ideas on entrepreneurial and autonomous work and above all to have improved their skills in the previously mentioned fields. Some of the participants tested their business ideas and the results were good. Not all participants could turn their business ideas into reality. Also, discovering work possibilities in one’s own municipality hit a low score (for example, 55/100 in Turin). However, according to the feedback from the participants, they have acquired important knowledge and skills that they will use in their futurelife, studies and career.

For the young people, this was an opportunity to get a new social network and gain life skills. This was both an empowering and useful experience to mention in your CV. The project also gave them the tools to initiate things on their own and even to involve other young people in it. (Solna Youth Café, Sweden)

This project enables young people to look at themselves, to look at where they live and think about the future they want for themselves and their communities and it gives them skills to move from where they are to where they want to be. (UBELE, UK)

In Albenga, one participant with a migrant background became a member in the council board of the partner organisation; thus, YEPP Albenga has become the first youth association where migrants have a say and voice their needs to the community.

In Kristinestad, meeting a mayor and presenting her their ideas about Kristinestad as a town to live in was very empowering for young refugees. They also went to the schools to present the Welcomeship project and so participants learned to talk in front of the crowd, speak better English and Finnish and gained more confidence.

Welcomeship Nights, where course participants talked about their experience and engaged with the audience, attracted other young people who became curious and more aware of the role they also can have, being inspired by their peers. Also community stakeholders, e.g. local business leaders, community leaders and politicians saw the real impact of the project in the attitude of the participants and realized that they can and should be involved in creating policies or developing programmes and ideas to explore the topic in a more efficient and sustainable way.

They were able to learn from the young people on the perspectives of inclusion and some of the challenges they face as young migrants and entrepreneurs. The business leaders were able to comment on the business ideas of young people. They were also inspired to put more effort to introduce more inclusion and diversity in their businesses. In Germany, one entrepreneur sponsored some goods to the group as they tested their concept of an African-German restaurant.

Some course participants had a chance to travel abroad to the youth exchange in Albenga, Italy and the Final Conference in Berlin, which was very eye-opening in the broadest sense, as they learnt in a multicultural environment and made friends with many people from around the world. Some refugees who received a certificate of completion of the Welcomeship were granted permission to stay in Italy. Building groups where everybody felt included and welcome was one of the key achievements of the project and is a positive fundament for its continuity and sustainability.

The project teams stated that the project gave them an opportunity to make or strengthen the links with the new partners in their countries: YEPP Albenga became cooperation partner of Legacoop, Italian-wide confederation of social enterprises and participated in further seminars and exchanges on the topic of inclusion and entrepreneurship. In Italy, Portugal and Germany, this experience improved the relationship between the partner organisation and municipality.

Also, partner organisations became visible to the local community for their work and engagement on the topic. Residents became interested in the activities that project partners were implementing and supporting. The communities have benefited from the project since new initiatives and projects are being initiated creating more jobs for the young people and more collaboration work between local young people and refugees.

4.7. Challenges

The biggest challenge for the Welcomeship course was to reach out to the right target group. Project coordinators used a lot of time and effort in promoting the project and finding young people who actually were interested and committed to take part in a project with a course duration of 1 year. Trainer teams had to find motivational measures, which sometimes differed according to the age, expectations and experience of participants. Some examples: for locals, the possibility to take a course for the credit in the gymnasium was offered, for newcomers, learning more about the local community and host country. Motivation for all was a possibility to do a course for free; meet the experts; get to know more people from your surrounding; participate in the international exchange in Albenga; go on site visits and receive a certificate of completion.

These measures certainly helped, but maintaining the group became the next big challenge. There were dropouts in almost all the groups and some groups like in the UK or Portugal had to restart again. Providing the training throughout the six months period was difficult for both participants and organizers to manage. A good practice was a residential training in Germany for a whole week so that participants could fully focus and concentrate on studying.

In Turin, we chose a target group that was too wide, both with regard to the community outreach and the “migrant” category. The course covered a neighborhood of 200,000 people, however none of the participants resided in this area. They all came from either other neighbourhoods in Turin or surrounding towns or international students. Then, the category “migrants” was very wide as it encompasses recently arrived asylum seekers, as well as the second generation of young people born in Italy from foreign parents, and foreigners only de-jure who identify as Italians in all aspects. The migrants who enrolled in the course were all highly educated and with high entrepreneurship expectations, so they were more interested in an incubator than in our basic non-formal learning course. Most migrants therefore left the course after the first meeting. In the end, the group that participated in the full course was composed of about 75% of Italians, of which some were NEETs and some were in their last years of university and with unclear ideas about career prospects. The remaining 25% of foreigners consisted partly of second generation migrants, partly of residents with migrant background who were already working or studying, therefore well integrated, plus a refugee and a Peruvian exchange student (CISV, Italy).

Another difficulty was the language barrier between newcomers and locals. First, it was difficult to deliver the topics in this course to participants who had difficulties in basic understanding of what is entrepreneurship, how to set up a business, how to make a pitch, and so on. Young refugees were not ready to take in all the given information because of posttraumatic stress and language barrier. In Kristinestad, and to some extent in Germany and Italy, local young people dropped out after the first modules because they felt that this project didn’t provide them with anything new, they already had entrepreneurial courses in school. Despite the discussion about inclusion and collaboration as a main point of the project, they were not so interested. Therefore the local teams had to continue the course with more migrants than locals.

Content-wise, the trainers had to adapt the course to deliver the message to participants in an appealing way. Despite all the content available online on the Welcomeship learning platform, it wasn’t appealing enough for young people to use it for study and for more information.

We had to make module 4 and 5 very easy. The content is difficult, and it was better have to have an understanding of the enterprises in Kristinestad. We felt we needed to do these modules in a way that suited best the group. So we worked on the idea of having a cultural café, and we organized it in June 2019, using the business canvas model from the Welcomeship course and bringing this idea to life. We finished the course in the summer and after the Open Garden event and cultural café we had contact with the group during summer time, but now mostly everybody has moved to study in another city. We are stillmantaining contact through Whatsapp, and we will meet again for the Multiplier Event in winter 2019 (Youth Office Kristinestad, Finland).

4.8. Suggestions for improvement

The general feedback of the trainers and coordinators to the question “If you were to do this project again…what would you do differently?” is highly positive. All the activities of the project were described as useful and well-designed. Especially the transnational blended youth exchange in Albenga was a key milestone for success. It brought young people, trainers and coordinators together to exchange their local implementation of the project and it facilitated sharing of experiences and peer learning.

If the teams were to do this project again, they would:

- Turn to a more defined target group, e.g. to newcomers instead of migrants, which is a very general term,

- Communicate the non-formal characteristics of our course and the difference with the “classic” courses on entrepreneurship,

- Involve more local youth in the project,

- Have residential training (“intensive week”) vs monthly workshops and then add different elements like study visits, meetings with sponsors and partners, community meetings (Welcomeship Nights) to support young people’s projects in practice and during the implementation phase,

- Plan for more informal interaction beyond the study sessions,

- Plan incubation period for the ideas to be developed and materialized and include seed funding.

In Cologne, only the Inclusion restaurant entrepreneurship idea is being materialized. It turned out to be more effective since the idea was developed under two projects and since the Deliot Stiftung co-funded its seed funding and the incubation period. Hence, for the business ideas under the Welcomeship project to be reality, there is a need to assign initial funding for the business ideas as we use a mechanism for long-term incubation of the ideas. These are the two components we suggest to be added in the future for similar projects (Migrafrica, Germany).

4.9. Teams say “What did we learn from the project?”

We learnt how powerful it is to work with people with different backgrounds and experiences as a group (YEPP Albenga, Italy).

We learned that it is not easy to break barriers and prejudices, but with small steps we can change someone’s life for the better. We learnt that this project has had a huge impact on young people who took part in the Welcomeship course. We learnt how important it is to give the migrants a feeling of being seen and heard and included as important people in the community. We think that it can lower the anxiety and stress levels that these people are often dealing with (Youth Office Kristinestad, Finland).

We realized through the project that young people have a lot of ideas but very often they don’t know how to implement them or whom to ask for support. We created a new programme called “Youth Initiatives Programme”. This programme aims to support young people in financial and logistical areas of idea development. In this way, we intend to give recognition to young people’s projects to build up their ownership and sense of belonging to their spaces. (DYPALL, Portugal)

Our main lesson is that community entrepreneurship needs an ongoing promotion and engagement of all stakeholders. Young people need further support after the training so they can realise their ideas. We need to create mechanisms in which the trained young people can further develop their business ideas in collaboration with entrepreneurship support centres. Also follow up projects are needed to guarantee the sustainability of the project. More training is needed but in a more compact form (Migrafrica, Germany).

Need for further action and learning

Given the importance of intercultural dialogue, most trainers see the need for the Welcomeship curriculum to be implemented in schools to increase the outreach to young people and teachers, and build consistency of the classes. In addition to building young people’s skills and competences in community-based entrepreneurship, teachers and school staff would strengthen their capacities and competences in building inclusive schools as micro-communities where everyone is respected as an individual.

5. Policy Recommendations local level

The following recommendations are created based on research, feedback, input and involvement of local policy makers, politicians and other stakeholders through the conducted surveys, organized Welcomeship Nights, video interviews and local and international debates and exchanges.

The drafted recommendations aim to provide potential proposals on how decision makers should enhance welcome culture and how different stakeholders should value ethnic minorities’ potential in their local communities. This set of recommendations also provides possible solutions on how youth organizations could reach out to young people with migrant background and thus implement activities that would result in more direct beneficiaries and long-lasting impact on inclusion of disadvantaged youth.

5.1. Decision makers: establish the welcome culture

Decision makers in the local communities sometimes are the most reachable level for young people and youth organizations when it comes to available mechanisms for inclusion of people with migrant background. This set of recommendations aims at providing potential solutions on how decision makers should enhance welcome culture in their communities.

- Decision makers should launch media literacy programmes to address prejudices, stereotypes and fake news related to people with migrant background and educate young people, local stakeholders and the media to recognize and raise voice against fake news.

- Despite the fact that people with migrant background do not have the right to vote, they are an important part of society and they need to be consulted about key issues important for their everyday life (education, social care, health care, housing, etc.). For that purpose, consultative meetings should be carried out at the local, regional and national level.

- Based on migrants’ assessed needs and competences, decision makers should work together in developing and implementing adequate strategies, policies and action plans which would tackle key priorities and bridge identified gaps for further integration and inclusion of people with migrant background.

- Institutions in charge should enhance interaction among young people with different backgrounds, including those living in the refugee centers, through different social activities that involve young people regardless of their origin, citizenship or language they speak.

- School authorities should organize different support groups, which could help students with migrant background to feel more accepted by sharing their culture, history, values and thus to foster further inclusion in the community.

- School authorities should integrate information, or a course, on community-based entrepreneurship in their curriculum to enhance collaboration among young people with different backgrounds through mutual development of potential business ideas.

- Decision makers should support welcome mechanisms for people at the local level regardless of their origin and background in order to support them to get to know each other better and thus to break existing prejudices and stereotypes. This would resultin introducing each other todifferent spheres of interest regarding their country of origin, political context, history, tradition and other actual topics.

- Decision makers should embrace a culture of dialogue as opposed to a culture of fear through a structured dialogue with people of migrant background and respond to their needs by solving concrete issues and challenges and thus make them feel welcome.

5.2. Youth organizations: reach out to people with migrant background

Youth organizations should try to reach out not only to general youth, but also to people with fewer opportunities and different backgrounds. The migrant population usually feels excluded in many aspects at the local level. Youth organizations could create a new practice by integrating young people with migrant background within their activities, but also in their decision making processes.

- Youth organizations should appoint the newly arrived migrant leaders to act as cultural mediators and outreach workers with the role to bridge current gaps in sharing necessary information and boost mutual understanding for further joint engagements of young people with different backgrounds in the community.

- Youth organizations and people with a migrant background should establish a shared decision making process in order to transfer migrants’ needs and priorities into relevant projects and policies that will respond to those needs and thus ensure sustainable inclusion.

- Based on the assessed needs, interests and acquired competences of people with migrant background, youth organizations should incentivize various intercultural activities (educational, sport, cultural, leisure activities, etc.) that could contribute to improved social cohesion in the local community.

- Youth organizations should initiate a holistic approach of different stakeholders (educational and public intuitions, local authorities, NGOs, social welfare service, etc.) in identifying the needs of people with migrant background and proposing a comprehensive set of activities to ensure their sustainable integration in the community instead of project-driven engagement of migrants.

- Youth organizations should involve more people with migrant background into decision making processes within the formal governing bodies of their organizations (e.g. Governing and Steering Committees). They shouldn’t limit them only to migrant issues, but also provide them with equal rights to share their views on a general scope of work of an organization.

- Youth organizations should empower cultural exchanges within the communities that will bridge language barriers among young people with different backgrounds, which will result in mutual learning, understanding and inclusion.

- Youth organizations together with other relevant stakeholders should focus on continuous development of young migrants’ entrepreneurial mindset through the tailor-made models that provide key information for easier and long-lasting integration.

5.3. Local stakeholders: value potential of ethnic minorities

A migrant community brings diversity to a local society and thus makes it more resilient to combat xenophobia and nationalism. A true partnership among young people with migrant background, youth organizations, decision makers and other stakeholders could result in sustainable inclusion of disadvantaged youth through understanding of their potential and responding to their needs.

- Youth organizations and local decision makers should lobby together for legislation change in order to introduce a “migrant quota” for ethnic minorities in the companies to enhance their employment and thus to further enable their inclusion.

- Local stakeholders should launch and support a series of intercultural events to help locals to get to know better ethnic minorities, their culture and traditions through storytelling, sport and leisure activities.

- Local stakeholders should conduct the mapping of migrants’ competences and skills to create a database that would serve potential employers who look for the workforce. This will enhance new employment and thus contribute to further inclusion of ethnic minorities and other people with migrant background in a more sustainable manner.

- School authorities together with youth organizations and people with migrant background should launch various learning programmes that will raise awareness of students and teachers regarding the importance of inclusion of ethnic minorities, refugees, migrants and asylum seekers.

- The relevant stakeholders should create multifunctional social hubs to empower local youth with different backgrounds develop innovative ideas and initiatives directed towards creation of welcome culture in their communities.

- Through joint celebration of important dates and holidays, local communities should raise awareness about the importance of diversity and thus to support inclusion of ethnic minorities through acceptance of their cultural and social models.

6. Policy Recommendations European level

6.1. Inclusion of people with migrant background

A number of factors can impact how people perceive migrants and to what extent they feel accepted in the local community. It’s of significant importance to enhance active participation of migrants and refugees in local economies, politics, arts, sports, public institutions, volunteering and other fields they have shown interest.

This could contribute in defeating stereotypes and prejudges that could easily lead to further segregation of people with migrant background particularly in education and employment. Since 2016, the European Commission has supported EU Member States in their efforts to include migrants in their education and training systems – from early childhood education and care to higher education.

It’s important to empower local governments and NGOs to serve as a bridge between local citizens and newly arrived inhabitants to help them to understand each other’s language, culture, traditions and make them integrated within all social aspects.

Refugees, asylum seekers and non-EU migrants are especially likely to be unemployed or under-employed. Using community-based entrepreneurship as an approach, local communities could work together with local businesses and other stakeholders to foster openness to employing migrants and refugees and thus to actively contribute to their long-term inclusion.

Difficulties that migrant entrepreneurs have in running a business

The difficulties that migrant entrepreneurs have in running a business is due to some specific obstacles that migrants – similarly as other vulnerable groups – face when they want to start a business.

- Usually they are facing many challenges to get any loans from the financial institutions due to lack of any property to serve as a collateral mortgage that could guarantee return of a bank investment. This keeps them out of entering more profitable sectors.

- Migrant entrepreneurs have difficulties to deal with local administration and to understand all local and national regulations regarding registration, taxation, financial reporting, etc.

- Migrant entrepreneurs in most of the cases are isolated from local business community which makes it even harder to understand local context and familiarize with the labour market. This is very hard to bridge due to the fact that they are most likely surrounded only by other migrants or people from underprivileged communities.

- As a result, migrants usually end up in low-profitable highly-demanding micro businesses which do not represent a decent form of employment in most of the cases.

Self-employment of immigrants in EU 2018-2019

According to the report Missing Policies (2019), the self-employment rate for immigrants in the European Union (EU) in 2018 was slightly below that of those born in the country of residence. Of the 18.5 million people that were born in another country working in the EU, about 13% were self-employed in 2018. This was slightly below the share of self-employed among those born in the reporting country (14.9%).

The number of self-employed immigrants increased in the EU from nearly 2.2 million in 2009 to 2.9 million in 2018 (these data exclude Germany because data are not available prior to 2017). This growth was driven by a 47% increase in the number of self-employed immigrant women. Despite the absolute increase in the number of self-employed immigrants, the self-employment rate was essentially constant between 2009 and 2018.

There is a substantial gender gap in self-employment for immigrants, which is consistent with the gender gap in the overall population of the self-employed. In the EU, immigrant men were about 1.5 times more likely than immigrant women to be self-employed in 2018 – 17.0% of working immigrant men born in another EU Member State and 16.2% of those born outside of the EU were self-employed relative to 10.3% and 9.4% of immigrant women. This is about the same as the overall gender gap in self-employment (16.9% vs. 9.6%).

Self-employment rates of immigrants varied substantially across the EU in 2018. Self-employment rates for immigrants were the highest in the Czech Republic (15.1% for those born in another EU Member State and 34.9% for those born outside of the EU) and the lowest in Norway (6.2% and 6.0%).

Overall, immigrant entrepreneurs in the European Union are about as likely to be job creators as non-immigrants. In 2018, 26.2% of the self-employed born outside of the EU had one or more employees, which was the same proportion as non-immigrant self-employed people (26.3%). However, those born in another EU Member State were slightly less likely to have employees (22.9%).

6.2. Recommendations for making inclusive policies

Inclusive financing strategies

European policies regarding integration and inclusion of migrants should be more holistic and coherent among the key partners in the EU in order to make sustainable solutions for long-lasting empowerment of welcome culture in the local communities. The allocated funds for these purposes should be blended with different support lines from other European financial institutions (e.g. European Investment Bank) and thus make these funds directly available to cities and municipalities to implement investments in sustainable local economic development through supporting community-based entrepreneurship and similar models of inclusive business.

Inclusive education

Young people with migrant background are facing many obstacles in their formal and non-formal education. In most EU countries, immigrant children and youth are in a disadvantaged position in the educational system. From their pre-school years, they are faced with challenges of non-acceptance and studying in a second language, which keeps them lagging behind their peers. These obstacles generally raise school dropout rate of young people with migrant background and consequently make them less competitive to enroll at a university or find a job.

European policy makers should focus on providing effective support for teachers and educators in implementing various inclusive education programmes together with practicing non-formal learning that would result with more young people with migrant background fully integrated in the educational system of the Member States.

Make migration and asylum regulations clear and available

Nowadays migrants are facing many obstacles during startup phase or while running a business regarding local and national legislation, taxation system, qualification recognition and informal skills assessment.

Relevant European institutions together with the Member States should create a virtual library/database that provides an overview of the current migration and asylum regulations concerning labour market access and residence rights of asylum seekers, refugees and other migrants.

6.3. Enhancing community-based entrepreneurship

In designing support measures for migrant entrepreneurship, different institutions and organizations should take into account existing instruments of support available in a given region or country that might help to tackle some of the specific obstacles faced by migrant entrepreneurs.

After taking into consideration current instruments to support migrants and their further integration through employment, policy makers should initiate new support mechanisms based on assessed needs of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers and identified priorities of local business community and particularly labour market demand.

Mutual learning, cooperation and resource sharing among people with migrant background and local businesses will create sustainable communities without ethnic and national tensions based on stereotypes and prejudices.

Support to existing migrant-owned businesses

From the current migrant businesses, policy makers should create role models not only for people with migrant background, but generally for representatives of different disadvantaged groups.

In addition, it would be very useful to expand their commercial and professional network from migrant-only contacts to diversified contacts in the community to support them in making sustainable and profitable business that could contribute to their further inclusion in local economy.

Platforms for sharing experiences related to migrants’ inclusion and integration

The creation of different platforms for sharing experiences in local policy development through the Committee of Regions (CoR) and other EU institutions could result in a larger scale of applicable solutions for further inclusion of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers.

While some of the local authorities lack expertise in migrants’ integration, other local governments are very experienced and have provided continuous support to migrants, refugees and asylum seekers in the last years. This support has resulted in significant achievements in sustainable inclusion and integration of migrants. Sharing this experience in a systematic way could strengthen the capacities of local authorities to develop and implement a series of integration polices.

There is already a huge number of EU-funded projects that have supported sharing of experiences and mutual learning among the decision makers on national, regional and local level. However, this support usually has been limited to the duration of the project and thus in most of the cases it hasn’t provided transfer of knowledge and good practices in effective and efficient manner.

Provision of multilingual information and raising visibility of success stories among migrants

In response to the opportunities and challenges raised by the increasing number of young migrants and refugees in the European Union as stated in the Council’s Resolution, European institutions should invest more effort to support launching of multilingual information services (including multilingual websites).

Identified role models among entrepreneurs with migrant background should be involved in the development and implementation of these services. Sharing their success stories could be inspirational particularly for newcomers to participate in different activities in their local community and thus make them more included in the society. These newly developed services could also serve to raise visibility of the existing entrepreneurship support initiatives among the immigrant communities provided from European or national level.

Measure and monitor the impact of existing migrant entrepreneurship support schemes

European institutions and organizations should be more focused on impact measurement and monitoring regarding the activities that are directed towards continuous and sustainable integration and inclusion of people with migrant background.

Organization of training and mentoring, providing one-off funding opportunities and other means of in-kind support to migrants and refugees shouldn’t be a goal itself. Only sustainable mechanisms co-created between European, national and local stakeholders together with migrant representatives will results in comprehensive migrant integration firstly into the labour market and later in all other social spheres.